There are some games that are so simple, so pure, so fundamental that they feel like they were discovered, not invented. Go is a perfect example. Probably Tetris.

If I were to get really good at a game, I feel like such games would be more worthy of my time. It’s part of my game design philosophy to try and make games that are discovered, not invented.

When I started working on Miegakure, I had experimented a little bit with making higher-dimensional games and so I knew that the player would be looking along three vectors out of four (these vectors could be oriented any which way in 4D). Why did I chose to let the players see only along three dimensions (taking a 3D slice), and not project the entire four dimensions down to three, then to two for the screen?

First of all, I wanted the 4D world to feel like an extension of the 3D world we live in. What if our world actually had four dimension, but we didn’t know it? I love this idea of a mysterious fourth dimension, rumored, but never seen (that’s true in the real world too!). And as a player you are the only person you know that is capable of reaching it.

Second, if you use a projection a lot of objects are going to overlap on the screen, objects that you can’t actually touch because they are too far away. You could try to solve this problem by coloring objects differently based on where they are along the fourth dimension, but this is unnecessarily difficult to visually parse.

In retrospect, one thing that makes Miegakure special as compared to the few other 4D visualizations that exist is that it lets you touch the 4D objects as if they were real objects, and create entire 4D generalization of our world. This is something that is much harder to do using projections, which is the usual way of representing 4D objects, such as this more commonly seen, confusing-looking, projection of a Tesseract (the 4D equivalent of a cube).

Then there was the question, how should the player be allowed to move along the fourth, perpendicular vector? The obvious way would be to have the player press another couple of buttons to move up or down the 4D.

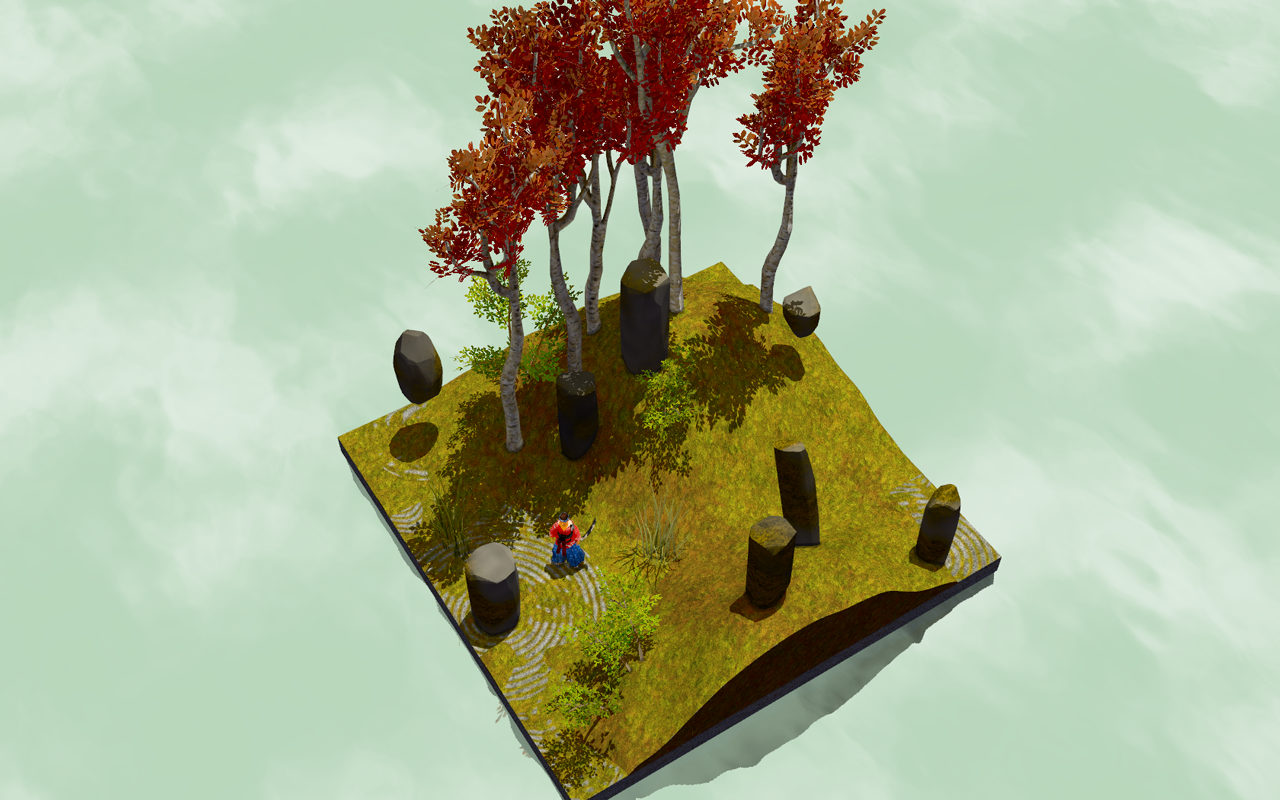

It quickly became clear that you don’t want the player to move blindly along the fourth direction; you want vision and movement to be coupled: if you could move without being able to see where you are going, you would bump into invisible objects, and the whole world would change at each step (In the 2D/3D version of the game shown on the right and in this trailer, if you could side-step the world you see would change at each step).

It quickly became clear that you don’t want the player to move blindly along the fourth direction; you want vision and movement to be coupled: if you could move without being able to see where you are going, you would bump into invisible objects, and the whole world would change at each step (In the 2D/3D version of the game shown on the right and in this trailer, if you could side-step the world you see would change at each step).

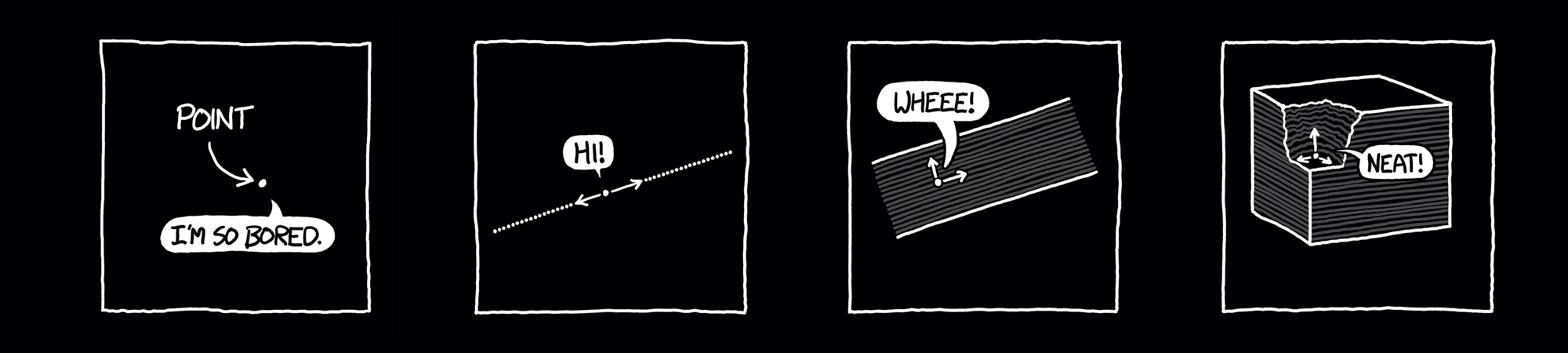

So the idea of swapping a dimension for the fourth one came about. Inspired by Ikaruga (which is a beautiful shooter where all the complexity is derived only from the ability to switch colors by pressing one button), the simplest thing you can do is to have one button that swaps a dimension for the fourth one back and forth.

I loved the idea that the game plays like a regular platformer, except for this one special button that you press once in a while. Braid is also this way.

If you are only allowed to move along three dimensions, but you can pick which ones they are, then you can move anywhere in 4D. The following question remains: which direction will be swapped for the fourth one? If you name the three dimensions X,Y,Z,W, and decide that gravity will point down Z, then you don’t want to swap Z out, because it would look very confusing, and pressing the jump button should probably always move you in Z. So you’re left with swapping either X or Y. If doesn’t really matter which one we pick, in my case it’s Y. For simplicity X is left untouched. It would not be interesting enough to let players swap in the X direction to justify adding that ability. It also means that levels can be made harder or easier by simply rotating them 90 degrees in the XY plane (i.e. swapping X and Y)!

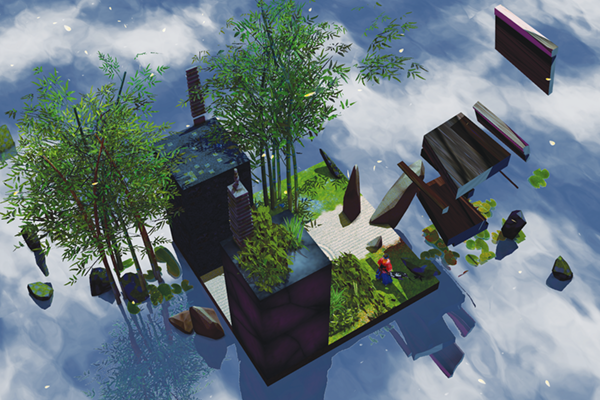

It turns out that a swap can be implemented as a 90 degree rotation, which can be interpolated smoothly (this is what is happening when the world looks like it is deforming).

As you can see, from first principles there was only one way to design Miegakure, and even though I was especially lucky in this case, that was very much something that I was trying to do. The rest was just exploration of this rule set.

But the next problem was: how do you make it so that the interactions are meaningful? 4D space is exponentially harder to fill with meaningful stuff. It takes 102=100 data points to fill a 10×10 grid, 103=1000 data points to fill a 10x10x10 grid, and 104=10000 data points to fill a 10x10x10x10 grid! This means that even if we take a small region of 4D space (10 units in each direction), we need a huge number of things to fill it with.

We want the number of objects to keep track of to be small to help the player hold them in their head. This essentially means that we want our “base” (the number that is raised to the power 4) to be small. This is how building the game out of 4D tiles, some of them pushable, with small levels (4x4x7x4 for example) came about. (Note that other, more detailed objects can always be placed on the tiles).

I think I may have been partly inspired by this puzzle from Braid (probably my favorite in the game!). The entire puzzle can fit on the screen; it’s just two doors and a key. It is extremely compressed. Everything extraneous to the puzzle itself has been removed. But it is still interesting and difficult to solve. All the difficulty is in the understanding of the systems at play, such that when you understand them properly the puzzle becomes trivial. (A video of it, spoilers!).

Because the number of objects to keep track of is small, it’s possible for the player to hold an entire level in their head. This is very important to me, because that means they are truly thinking in 4D, as opposed to looking at a bunch of 3D spaces one at a time.

At this point I could vaguely picture how to walk through walls using the fourth dimension in my head. I knew that since two dimensions are always visible an entire plane would stay the same after rotating, and therefore objects on this plane would be reference points, and that they would help the players orient themselves.

So I didn’t really know what the game would look like! I especially could not picture how the transition between the two states would look like. But I programmed it and found out and I was the first person to discover how to play the game.